gynea&obs

Monday, 21 March 2011

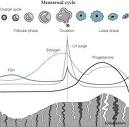

Menstrual Cycle

Menstruation is the shedding of the lining of the uterus (endometrium) accompanied by bleeding. It occurs in approximately monthly cycles throughout a woman's reproductive life, except during pregnancy. Menstruation starts during puberty (at menarche) and stops permanently at menopause .

By definition, the menstrual cycle begins with the first day of bleeding, which is counted as day 1. The cycle ends just before the next menstrual period. Menstrual cycles normally range from about 25 to 36 days. Only 10 to 15% of women have cycles that are exactly 28 days. Usually, the cycles vary the most and the intervals between periods are longest in the years immediately after menarche and before menopause.

Menstrual bleeding lasts 3 to 7 days, averaging 5 days. Blood loss during a cycle usually ranges from ½ to 2½ ounces. A sanitary pad or tampon, depending on the type, can hold up to an ounce of blood. Menstrual blood, unlike blood resulting from an injury, usually does not clot unless the bleeding is very heavy.

The menstrual cycle is regulated by hormones. Luteinizing hormone and follicle-stimulating hormone, which are produced by the pituitary gland, promote ovulation and stimulate the ovaries to produce estrogen and progesterone Some Trade Names

CRINONEENDOMETRIN

. Estrogen and progesterone Some Trade Names

CRINONEENDOMETRIN

stimulate the uterus and breasts to prepare for possible fertilization. The cycle has three phases: follicular (before release of the egg), ovulatory (egg release), and luteal (after egg release).

CRINONEENDOMETRIN

. Estrogen and progesterone Some Trade Names

CRINONEENDOMETRIN

stimulate the uterus and breasts to prepare for possible fertilization. The cycle has three phases: follicular (before release of the egg), ovulatory (egg release), and luteal (after egg release).

| |||||||

Follicular Phase: This phase begins on the first day of menstrual bleeding (day 1). But the main event in this phase is the development of follicles in the ovaries.

At the beginning of the follicular phase, the lining of the uterus (endometrium) is thick with fluids and nutrients designed to nourish an embryo. If no egg has been fertilized, estrogen and progesterone Some Trade Names

CRINONEENDOMETRIN

levels are low. As a result, the top layers of the endometrium are shed, and menstrual bleeding occurs.

CRINONEENDOMETRIN

levels are low. As a result, the top layers of the endometrium are shed, and menstrual bleeding occurs.

About this time, the pituitary gland slightly increases its production of follicle-stimulating hormone. This hormone then stimulates the growth of 3 to 30 follicles. Each follicle contains an egg. Later in the phase, as the level of this hormone decreases, only one of these follicles (called the dominant follicle) continues to grow. It soon begins to produce estrogen, and the other stimulated follicles begin to break down.

On average, the follicular phase lasts about 13 or 14 days. Of the three phases, this phase varies the most in length. It tends to become shorter near menopause. This phase ends when the level of luteinizing hormone increases dramatically (surges). The surge results in release of the egg (ovulation).

Ovulatory Phase: This phase begins when the level of luteinizing hormone surges. Luteinizing hormone stimulates the dominant follicle to bulge from the surface of the ovary and finally rupture, releasing the egg. The level of follicle-stimulating hormone increases to a lesser degree. The function of the increase in follicle-stimulating hormone is not understood

The ovulatory phase usually lasts 16 to 32 hours. It ends when the egg is released.

About 12 to 24 hours after the egg is released, the surge in luteinizing hormone can be detected by measuring the level of this hormone in urine. This measurement can be used to determine when women are fertile. The egg can be fertilized for only up to about 12 hours after its release. Fertilization is more likely when sperm are present in the reproductive tract before the egg is released.

Around the time of ovulation, some women feel a dull pain on one side of the lower abdomen. This pain is known as mittelschmerz (literally, middle pain). The pain may last for a few minutes to a few hours. The pain is felt on the same side as the ovary that released the egg, but the precise cause of the pain is unknown. The pain may precede or follow the rupture of the follicle and may not occur in all cycles. Egg release does not alternate between the two ovaries and appears to be random. If one ovary is removed, the remaining ovary releases an egg every month.

Luteal Phase: This phase begins after ovulation. It lasts about 14 days (unless fertilization occurs) and ends just before a menstrual period. In this phase, the ruptured follicle closes after releasing the egg and forms a structure called a corpus luteum, which produces increasing quantities of progesterone Some Trade Names

CRINONEENDOMETRIN

. The corpus luteum prepares the uterus in case fertilization occurs. The progesterone Some Trade Names

CRINONEENDOMETRIN

produced by the corpus luteum causes the endometrium to thicken, filling with fluids and nutrients to nourish a potential fetus. Progesterone Some Trade Names

CRINONEENDOMETRIN

causes the mucus in the cervix to thicken, so that sperm or bacteria are less likely to enter the uterus. Progesterone Some Trade Names

CRINONEENDOMETRIN

also causes body temperature to increase slightly during the luteal phase and remain elevated until a menstrual period begins. This increase in temperature can be used to estimate whether ovulation has occurred During most of the luteal phase, the estrogen level is high. Estrogen also stimulates the endometrium to thicken.

CRINONEENDOMETRIN

. The corpus luteum prepares the uterus in case fertilization occurs. The progesterone Some Trade Names

CRINONEENDOMETRIN

produced by the corpus luteum causes the endometrium to thicken, filling with fluids and nutrients to nourish a potential fetus. Progesterone Some Trade Names

CRINONEENDOMETRIN

causes the mucus in the cervix to thicken, so that sperm or bacteria are less likely to enter the uterus. Progesterone Some Trade Names

CRINONEENDOMETRIN

also causes body temperature to increase slightly during the luteal phase and remain elevated until a menstrual period begins. This increase in temperature can be used to estimate whether ovulation has occurred During most of the luteal phase, the estrogen level is high. Estrogen also stimulates the endometrium to thicken.

The increase in estrogen and progesterone Some Trade Names

CRINONEENDOMETRIN

levels causes milk ducts in the breasts to widen (dilate). As a result, the breasts may swell and become tender.

CRINONEENDOMETRIN

levels causes milk ducts in the breasts to widen (dilate). As a result, the breasts may swell and become tender.

If the egg is not fertilized, the corpus luteum degenerates after 14 days, and a new menstrual cycle begins. If the egg is fertilized, the cells around the developing embryo begin to produce a hormone called human chorionic gonadotropin. This hormone maintains the corpus luteum, which continues to produce progesterone Some Trade Names

CRINONEENDOMETRIN

, until the growing fetus can produce its own hormones. Pregnancy tests are based on detecting an increase in the human chorionic gonadotropin level.

CRINONEENDOMETRIN

, until the growing fetus can produce its own hormones. Pregnancy tests are based on detecting an increase in the human chorionic gonadotropin level.

Friday, 11 March 2011

detail of Female Internal Genital Organs

The Female Internal Genital Organs

The Vagina

The Relations of the Vagina

The Sphincters of the Vagina

The Arterial Supply of the Vagina

The Venous Drainage of the Vagina

The Lymphatic Drainage of the Vagina

Innervation of the Vagina

The Uterus

Click here for a schematic diagram of the uterus.

The Fundus of the Uterus

The Cervix of the Uterus

The Isthmus of the Uterus

The Wall of the Uterus

Surfaces and Borders of the Uterus

The Ligaments of the Uterus

Click here for schematic diagrams of the ligaments of the uterus.

Transverse Cervical Ligament (Cardinal Ligament)

The Uterosacral Ligaments

The Round Ligament of the Uterus

The Broad Ligament

The Principal Support of the Uterus

The Relationships of the Uterus

Arterial Supply of the Uterus

Venous Drainage of the Uterus

Lymphatic Drainage of the Uterus

Innervation of the Uterus

The Uterine Tubes

The Infundibulum of the Uterine Tube

The Ampulla of the Uterine Tube

The Isthmus of the Uterine Tube

The Intramural (Uterine) Part of the Uterine Tube

The Mesosalpinx

Arterial Supply of the Uterine Tubes

Venous Drainage of the Uterine Tubes

Lymphatic Drainage of the Uterine Tubes

Innervation of the Uterine Tubes

- The genitalia or genital organs consist of internal and external structures.

- The female internal genital organs include the vagina, uterus, uterine tubes and ovaries.

The Vagina

- This is the female organ of copulation and is a fibromuscular tube or sheath lined with stratified squamous epithelium.

- It forms the inferior portion of the female genital tract and the birth canal.

- It extends from the cervix of the uterus to the vestibule of the vagina.

- The vagina communicates superiorly with the cervical canal and opens inferiorly into the vestibule of the vagina.

- In the anatomical position, the vagina descends anteroinferiorly.

- Its anterior and posterior walls are normally in apposition, except at its superior end where the cervix of the uterus enters its cavity.

- The posterior wall is about 1 cm longer than the anterior wall and is in contact with the external uterine ostium (external os).

- The vagina is located posterior to the urinary bladder and anterior to the rectum and passes between the medial margins of the levator ani muscles.

- It pierces the urogenital diaphragm with the sphincter urethrae muscle.

- The posterior fibres of the sphincter urethrae muscle are attached to the vaginal wall.

- The cervix of the uterus projects into the superior part of the anterior wall, separating the walls of the vagina.

- The uterus lies almost at a right angle to the axis of the vagina (anteverted position). This uterine angle increases as the urinary bladder fills.

- The vaginal recess around the cervix is called the fornix (L. arch).

- It is divided into anterior, posterior, and lateral parts.

- The posterior part of the fornix is the deepest and is related to the rectouterine pouch.

The Relations of the Vagina

- Its anterior wall is in contact with the cervix, the fundus of the bladder, the terminal parts of the ureters, and the urethra.

- The superior limit of the vagina is the 1 to 2 cm of its posterior wall covering the posterior part of the fornix.

- This part is usually covered by peritoneum.

- A penetrating wound to this part of the vagina may involve the peritoneal cavity.

- Inferior to the posterior part of the fornix, there is only the loose connective tissue of the rectovaginal septum separating the posterior wall from the rectum.

- This then can be palpated in the rectum.

- The vagina is related inferiorly to the perineal body.

- The narrow lateral walls of the vagina in the region of the fornix are attached to the broad ligament of the uterus.

- Inferiorly, the lateral walls of the vagina are in contact with the levator ani muscles, the greater vestibular glands, and the bulbs of the vestibule.

- Contraction of the pubococcygeus parts of the levator ani muscles draws the lateral walls of the vagina together.

The Sphincters of the Vagina

- There are 3 muscles that can compress the vagina and act like sphincters:

- The pubovaginalis muscle, the anterior part of the levator ani;

- The urogenital diaphragm;

- And the bulbospongiosus muscle.

The Arterial Supply of the Vagina

- The vaginal artery is usually a branch of the uterine artery.

- It may, however, arise from the internal iliac artery.

- The 2 vaginal arteries anastomose with each other and with the cervical branch of the uterine artery.

- The internal pudendal artery and vaginal branches of the middle rectal artery also supply the vagina (branches of the internal iliac arteries).

- These arteries form anterior and posterior azygos arteries to supply the vaginal wall.

The Venous Drainage of the Vagina

- The vaginal veins form vaginal venous plexuses along the sides of the vagina and within its mucosa.

- Drainage is into the internal iliac veins.

- They communicate with the vesical, uterine, and rectal venous plexuses.

The Lymphatic Drainage of the Vagina

- The lymph vessels from the vagina are in 3 groups:

- Those from the superior part accompany the uterine artery and drain into the internal and external iliac lymph nodes;

- Those from the middle part accompany the vaginal artery and drain into the internal iliac lymph nodes;

- And those from the vestibule drain into the superficial inguinal lymph nodes.

- Some lymph from the vestibule drain into the sacral and common iliac lymph nodes.

Innervation of the Vagina

- The vaginal nerves are derived from the uterovaginal plexus.

- This lies in the base of the broad ligament on each side of the supravaginal part of the cervix.

- The inferior nerve fibres from this plexus supply the cervix and the superior part of the vagina.

- The fibres supplying the vagina are derived from the inferior hypogastric plexus and the pelvic splanchnic nerves.

- The inferior part of the vagina is supplied by the pudendal nerve.

The Uterus

Click here for a schematic diagram of the uterus.

- This is a hollow, thick-walled, pear-shaped muscular organ located between the bladder and the rectum (in non-pregnant women).

- It is 7 to 8 cm long, 5 to 7 cm wide, and 2 to 3 cm thick.

- The uterus normally projects superoanteriorly over the urinary bladder.

- During pregnancy, the uterus enlarges greatly to accommodate the embryo and later the foetus.

- The uterus consists of 2 major parts:

- The expanded superior 2/3 is known as the body;

- The cylindrical inferior 1/3 is called the cervix (L. neck).

- The uterus is usually bent anteriorly (anteflexed) between the cervix and body.

- The entire uterus is normally bent or inclined anteriorly (anteverted).

- It is frequently retroverted (inclined posteriorly) in older women.

The Fundus of the Uterus

- The fundus of the uterus is the rounded superior part of the body.

- It is located superior to the line joining the points of entrance of the uterine tubes.

- The regions of the body where the uterine tubes enter are called the cornua (L. horns).

The Cervix of the Uterus

- As the cervix projects into the vagina, it is divided into vaginal and supravaginal parts.

- The rounded vaginal part communicates with the vagina via the external ostium of the uterus (L. ostium, door, entrance or mouth).

- The ostium is bounded by anterior and posterior lips formed by the cervix.

The Isthmus of the Uterus

- This is about 1 cm long and is the narrow transitional zone between the body and cervix.

- This slight constriction is most obvious in nulliparous women.

The Wall of the Uterus

- The wall of the uterus consists of 3 layers:

- The outer serous coat called the perimetrium, consists of peritoneum supported by a thin layer of connective tissue;

- The middle muscular coat called the myometrium consists of 12 to 15 mm of smooth muscle. The myometrium increases greatly during pregnancy. The main branches of the blood vessels and nerves of the uterus are located in this layer;

- The inner mucous coat called endometrium is firmly adherent to the underlying myometrium.

- The endometrium is partly sloughed off each month during menstruation.

- It lines only the body of the uterus.

Surfaces and Borders of the Uterus

- The uterus has an anteroinferior or vesical surface related to the urinary bladder.

- There is also a posterosuperior or intestinal surface related to the intestine.

- These convex surfaces are separated by right and left borders.

- Each uterine tube enters the lateral border of the body of the uterus near its superior end.

- The tube opens at one end into the peritoneal cavity near the ovary and at the other end into the uterine cavity.

- The ligaments of the ovaries are attached to the uterus, posteroinferior to the uterotubal junctions.

- The round ligaments of the uterus are attached anteroinferiorly to these junctions.

The Ligaments of the Uterus

Click here for schematic diagrams of the ligaments of the uterus.

Transverse Cervical Ligament (Cardinal Ligament)

- This extends from the cervix and lateral parts of the vaginal fornix to the lateral walls of the pelvis.

The Uterosacral Ligaments

- These pass superiorly and slightly posteriorly from the sides of the cervix to the middle of the sacrum.

- They are deep to the peritoneum and superior to the levator ani muscles.

- The uterosacral ligaments tend to hold the cervix in its normal relationship to the sacrum.

The Round Ligament of the Uterus

- These ligaments are 10 to 12 cm long and extend for the lateral aspect of the uterus, passing anteriorly between the layers of the broad ligament.

- They leave the abdominal cavity through the inguinal canal and insert into the labia majora.

The Broad Ligament

- This is a fold of peritoneum with mesothelium on its anterior and posterior surfaces.

- It extends from the sides of the uterus to the lateral walls and floor of the pelvis.

- The broad ligament holds the uterus in its normal position.

- The 2 layers of the broad ligament are continuous with each other at a free edge.

- This is directed anteriorly and superiorly to surround the uterine tube.

- Laterally, the broad ligament is prolonged superiorly over the ovarian vessels as the suspensory ligament of the ovary.

- The ovarian ligament lies posterosuperiorly and the round ligament of the uterus lies anteroinferiorly within the broad ligament.

- The broad ligament contains extraperitoneal tissue (connective tissue and smooth muscle) called parametrium.

- It gives attachment to the ovary through the mesovarium.

- The mesosalpinx is a mesentery supporting the uterine tube.

The Principal Support of the Uterus

- This is the pelvic floor, formed by the pelvic diaphragm.

- The pelvic viscera surrounding the uterus and the visceral fascia (endopelvic fascia) bind the pelvic viscera together.

- The two levator ani muscles, the two coccygeus muscles, and the muscles of the urogenital diaphragm are particularly important in supporting the uterus.

The Relationships of the Uterus

- Anteriorly the body of the uterus is separated from the urinary bladder by the vesicouterine pouch.

- Here, the peritoneum is reflected from the uterus onto the posterior margin of the superior surface of the bladder.

- The vesicouterine pouch is empty when the uterus is in its normal position.

- Posteriorly the body of the uterus and the supravaginal part of the cervix are separated from the sigmoid colon by a layer of peritoneum and the peritoneal cavity.

- The uterus is separated from the rectum by the rectouterine pouch (of Douglas).

- The inferior part of this pouch is closely related to the posterior part of the fornix of the vagina.

- Laterally the relationship of the ureter to the uterine artery is very important.

- The ureter is crossed superiorly by the uterine artery at the side of the cervix.

Arterial Supply of the Uterus

- This is derived mainly from the uterine arteries, which are branches of the internal iliac arteries.

- They enter the broad ligaments beside the lateral parts of the fornix of the vagina, superior to the ureters.

- At the isthmus of the uterus, the uterine artery divides into a large ascending branch that supplies the body of the uterus and a small descending branch that supplies the cervix and vagina.

- The uterus is also supplied by the ovarian arteries, which are branches of the aorta.

- The uterine arteries pass along the sides of the uterus within the broad ligament and then turn laterally at the entrance to the uterine tubes, where they anastomose with the ovarian arteries.

Venous Drainage of the Uterus

- The uterine veins enter the broad ligaments with the uterine arteries.

- They form a uterine venous plexus on each side of the cervix and its tributaries drain into the internal iliac vein.

- The uterine venous plexus is connected with the superior rectal vein, forming a portal-systemic anastomosis.

Lymphatic Drainage of the Uterus

- The lymph vessels of the uterus follow three main routes:

- Most lymph vessels from the fundus pass with the ovarian vessels to the aortic lymph nodes, but some lymph vessels pass to the external iliac lymph nodes or run along the round ligament of the uterus to the superficial inguinal lymph nodes.

- Lymph vessels from the body pass through the broad ligament to the external iliac lymph nodes.

- Lymph vessels from the cervix pass to the internal iliac and sacral lymph nodes.

Innervation of the Uterus

- The nerves of the uterus arise from the inferior hypogastric plexus, largely from the anterior and intermediate part known as the uterovaginal plexus.

- This lies in the broad ligament on each side of the cervix.

- Parasympathetic fibres are from the pelvic splanchnic nerves (S2-4), and sympathetic fibres are from the above plexus.

- The nerves to the cervix form a plexus in which are located small paracervical ganglia.

- One of these are large and is called the uterine cervical ganglion.

- The autonomic fibres of the uterovaginal plexus are mainly vasomotor.

- Most the afferent fibres ascend through the inferior hypogastric plexus and enter the spinal cord via T10-12 and L1 spinal nerves.

The Uterine Tubes

- These are 10 em long and 1 cm in diameter.

- They extend laterally from the cornua of the uterus.

- The uterine tubes carry oocytes from the ovaries and sperm cells from the uterus to the fertilisation site in the ampulla of the uterine tube.

- The uterine tube also conveys the dividing zygote to the uterine cavity.

- Each tube opens at its proximal end into the cornua or horn of the uterus.

- At its distal end, it opens into the peritoneal cavity near the ovary.

- The uterine tubes allow communication between the peritoneal cavity and the exterior of the body.

- The uterine tube is divided into 4 parts: infundibulum, ampulla, isthmus, and intramural or uterine parts.

The Infundibulum of the Uterine Tube

- This is the funnel-shaped lateral or distal end of the uterine tube.

- It is closely related to the ovary.

- Its opening into the peritoneal cavity is called the abdominal ostium.

- About 2 mm in diameter, the ostium lies at the bottom of the infundibulum.

- Its margins have 20 to 30 fimbriae (L. fringes).

- These finger-like processes spread over the surface of the ovary, and a large one, the ovarian fimbria, is attached to the ovary.

- During ovulation the fimbriae trap the oocyte and sweep it through the abdominal ostium into the ampulla.

The Ampulla of the Uterine Tube

- This begins at the medial end of the infundibulum.

- It is in this tortuous part that fertilisation of the oocyte by a sperm usually occurs.

- The ampulla is the widest and longest part of the uterine tube, making up over half of its length.

The Isthmus of the Uterine Tube

- This is the short (about 2.5 cm), narrow, thick-walled part of the uterine tube.

- It enters the cornu of the uterus.

The Intramural (Uterine) Part of the Uterine Tube

- This part of the tube is the short segment that passes through the thick myometrium of the uterus and opens via the uterine ostium into the uterine cavity.

- This opening is smaller than the abdominal ostium.

The Mesosalpinx

- The uterine tubes lie in the free edges of the broad ligaments of the uterus.

- The part of the broad ligament attached to the uterine tube is called the mesentery of the tube or mesosalpinx (G. salpinx, a tube).

- The uterine tubes extend posterolaterally to the lateral walls of the pelvis, where they ascend and arch over the ovaries.

- Except for their uterine parts, the uterine tubes are clothed in peritoneum.

Arterial Supply of the Uterine Tubes

- The arteries to the tubes are derived from the uterine and ovarian arteries.

- The tubal branches pass to the tube between the layers of the mesosalpinx.

Venous Drainage of the Uterine Tubes

- The veins of the tubes are arranged similarly to the arteries and drain into the uterine and ovarian veins.

Lymphatic Drainage of the Uterine Tubes

- The lymph vessels of the uterine tubes follow those of the fundus of the uterus and ovary and ascend with ovarian veins to the aortic lymph nodes in the lumbar region.

Innervation of the Uterine Tubes

- The nerve supply of the uterine tubes comes partly from the ovarian plexus of nerves and partly from the uterine plexus.

- Afferent fibres from the tubes are contained in T11-12 and L1 nerves.

development of the ovary

the development of the genital tract is in the female is from multiple sources .

the ovary drives its structure from three sources.

1)yolksac

2)coelomic epithelium

3)mesenchymal tissue

the ovary drives its structure from three sources.

1)yolksac

2)coelomic epithelium

3)mesenchymal tissue

the female internal genitalia

the internal genitalia organs are

1)vagina

2)uterus

3)fallopian tubes

4)ovaries

1)vagina

2)uterus

3)fallopian tubes

4)ovaries

the femaleexternal genitalia

the external genitalia are collectively known as vulva. the vulva includes the following parts.

!)mons veneris

2)labia majora

3)labia minora

4)clitorious

5)vestibule

6)hymen

7)perinium

8)bartholin s: gland

9)vestibular bulbs

!)mons veneris

2)labia majora

3)labia minora

4)clitorious

5)vestibule

6)hymen

7)perinium

8)bartholin s: gland

9)vestibular bulbs

Subscribe to:

Posts (Atom)